Today, most business processes are enabled through technology. That should ideally put technologists (read CIO and their teams) in an enviable position. But the reality is far from it – technology actually gets a pretty bad rap when it comes to such assessment from the business. Most often, from the business’s point of view, technology fails to create significant value, fails to deliver the promised efficiencies and the desired value on the investments. This is true for most major corporate IT initiative, whether they were a result of business driving technology or the other way around. Most supply chain initiatives have a large functional and organization footprint and therefore, often fall into a similar trap. But is technology really to blame for the low returns or is there more to it?

When firms invest in packaged business solutions, one of the most common and misguided expectations is that the solution will fully enable their existing processes. This is misguided because the packaged software solutions are built to provide only a certain amount of process support that is (1) common across industries and (2) generally considered the best practice in an industry/segment. None of which ensures that the solution will fully enable their existing processes. To make matters worse, such business initiatives generally do not involve any planned changes in the business process even when the existing processes do not fully support the needs. In fact, most of the initiatives do not involve any capability assessment to ensure that the business processes are designed to support the business strategy and the advantages it seeks to create.

No wonder, a large number of such ill-planned initiatives fail to produce the expected results. Jim Shepherd of Gartner (First Thing Monday column, 2/21/2011) estimated that 30% to 50% of ERP projects are thought to be “failures” by the people who were thinking of implementing one. But he says that this may just be another “urban myth” – because of the unrealistic expectations of the organization from a technology. He think that an ERP should be seen more like an “infrastructure” (enabling transaction processing, data management, process integration and information access) rather than the “streamlined (business) processes”. To quote him, “ERP should be viewed as the stable infrastructure that allows an organization to create and deploy the kind of innovation and differentiation that drives real business improvements”.

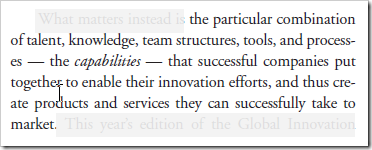

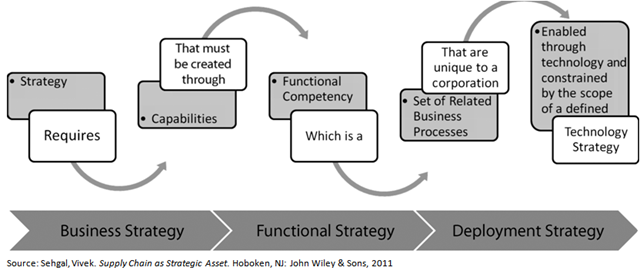

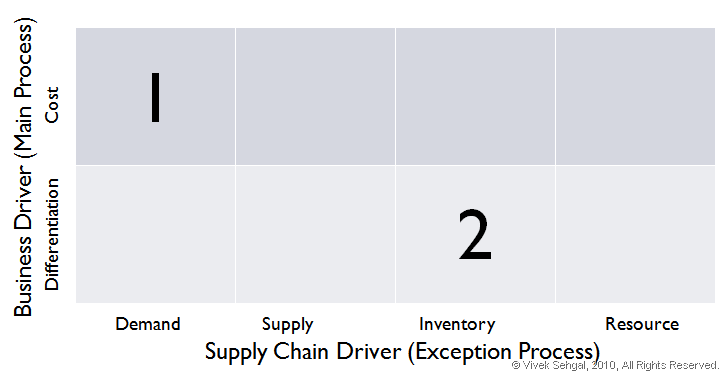

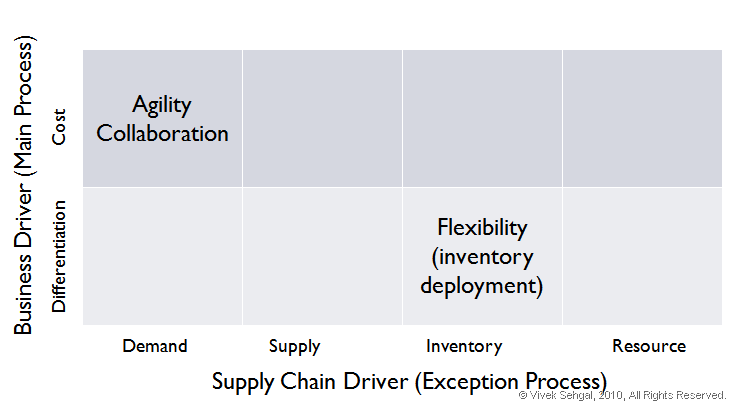

That is a view I fully support – technology is simply an enabler. The differentiation and hence the competitive advantages can be created only through business capabilities that are superior to others. Such superiority is never an accident, but must be a result of deliberate design of business processes that support your strategy. To learn about how you can assess your supply chain capabilities and drive competitive advantage by designing the right supply chain capabilities, continue reading on the subject in my book on supply chain strategy.

Related Articles:

- Building Capabilities to Win

- Best Practices- Not Good Enough

- Business Strategy & Supply Chains

- Business, Functional & Deployment Strategy Alignment for Supply Chains

- New Supply Chain Design Imperative

© Vivek Sehgal, 2011, All Rights Reserved.

Want to know more about supply chain processes? How they work and what they afford? Check out my books on Supply Chain Management at Amazon.